Historical Brass Instrument Making Research, Design, and Working Methods

Excerpts from a lecture given at the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Scotland Dec. 2008

Introduction

In the field of musical instrument making there has always been a working relationship between the performer and the instrument maker. In the area of historically informed performance there is yet another relationship, which is crucial to the making of period instruments. This is the relationship with those who preserve, document, and measure instruments in collections, supporting the instrument maker much in the same way that musicologists research performance practices of previous periods, giving performers the information they need to perform music in an historically informed way.

With the help of those involved in working with collections, I choose models to work with, measure them, and essentially design a horn. I then work with the design, so that the resulting instrument is not just a faithful copy, but a well designed and well thought out original in its own right.

Because I need to make brass instruments for living, working musicians, I must be a living, evolving horn maker, making instruments for use today, but in the style of another period. My intention as a maker is to start at the point where the original maker left off, as his apprentice might have done, and to be a maker of fine horns absolutely in the tradition of the original, - horns that will best represent the intentions of the composer and the aesthetics of the time, and would have been respected by players and enjoyed by audiences of the period.

In this lecture I would like to focus on several aspects of how a maker of historical instruments works with original instruments and collections to develop historical instrument models. I will use some of my own models as examples of how I go about gathering information and developing my designs, and also the alterations in design that my own needs as a player have inspired me to make.

Three models, and how they were developed

Of the several horn models that I make, I would like to use three that I make regularly as examples of the process of working out a design, and of my working methods:

English baroque orchestra horn based on an original by Christopher Hofmaster from sometime after 1750, which is an example of an instrument that I have copied as strictly as possible with very few alterations.

German baroque horn by Johann Wilhelm Haas in Nürnberg from the first half of the 18th century, which involved some speculation and original instrument design.

French classical horn based on an original from early in the 19th century made by Antoine Halari in Paris, which is the most precisely copied of all of the models I make, involving virtually no intentional alterations of the original design of the maker, but as we will see, the design necessarily becomes my own in each of these cases, simply by coming into my hands and being made by someone other than the original maker.

Photos of each of these can be seen on their respective pages on my website.

Christopher Hofmaster baroque horn

The Hofmaster baroque horn, EUCHMI # 3297 in the Edinburgh University Collection of Historic Musical Instruments, is one of the best examples that I’ve seen of the documentation of an instrument in a museum collection. Raymond Parks and Arnold Myers did a series of full scale drawings of the instrument and crooks along with measurements of the entire body section and all other tapered parts that are so complete and accurate that I felt comfortable enough to use that information to make my own copy of the instrument. The comparison of the copy to the original, which I was able to do on my second visit to Edinburgh in 2008, showed me that their work was extremely precise.

In the making of this horn, I was able to compare the work done on the Edinburgh horns with another Hofmaster horn that came into my own possession. And I’ve also been able to compare all of that information to the two Hofmaster horns in the Bate collection in Oxford.

After the copy of a particular instrument is made the moment of truth comes when you compare the copy to the original both in its playing qualities and its measurements. The bell of my copy was right on, according to the Edinburgh drawings, and the measurements that I did myself, but there were some discrepancies in the second half of the body, not due to Raymond Parks’ measurements, but due to my tool maker. I was able to fix these when I got home, by altering the mandrel that makes that section.

Alterations to the design that I’ve done to make this instrument useful for playing in period instrument ensembles would include:

Making it a right handed instrument, - the original was left-handed - essentially wrapping it up the other way to make it comfortable for those of us who are used to right handed instruments. This has absolutely no acoustical, effect and I found out during my visit to Oxford that one of the Bate collection instruments is right handed.

Making the crooks in the keys needed for baroque orchestra playing. The single remaining terminal crook (mouthpipe) was in the key of C alto, so I had to develop a mouthpipe taper that would play well as a G crook to be used in conjunction with the set of couplers. I looked at the mouthpipe taper from another English instrument by Nicholas Winkings from a similar period, but ultimately chose to use a taper that I already had that was similar, and played well.

The body section of the original horn was made in two pieces that were brazed together without a ferrule. I chose to make the instrument also in two pieces, but with a ferrule - a change that has minimal acoustical implications, since it doesn’t change the bore profile of the horn.

I think any London horn player of the mid 18th century would have been happy to play on the copy that I made and would have considered it a perfectly normal well made instrument in both its appearance and playing qualities.

As an option to customers who order the Hofmeister and Haas models, I sometimes add ventholes to both of them, so that the intonation of the 11th and 13th partials can be corrected when the horn is played without the hand in the bell, as is the practice in period instrument groups in the US and the UK. For those who are interested in the venthole controversy, I’ve written two papers on the subject of ventholes for the International Horn Society Journal and for the book of papers from the Musikinstrumentenbau Symposium at Michaelstein in Germany. We all play with ventholes, and though they did not exist at the time, for better or for worse, ventholes are part of the early brass world today for horn and trumpet players.

J. W. Haas baroque horn

The original of the Haas baroque horn, which is in a private collection, was made as a fixed pitch horn, probably in the key of F of the period. My intention in measuring this original was to develop a German baroque model with crooks that would play well in several of the common baroque keys, and be an appropriate instrument for Bach, Handel, Telemann, and other composers of the period whose music is played regularly by the period instrument ensembles with which I played.

Current research would suggest that fixed pitch horns were the norm for instruments before 1750, but if modern players were to insist on playing fixed pitch horns, each player would have to have several instruments to cover the most common baroque horn keys. For this reason, I make the Haas horn as a crooked instrument, though it can be made as a fixed pitch horn, as the original was.

The original of the Haas horn could not easily be used in musical ensembles due to its large, two coiled configuration, - and the fact that it can only play in one key. I chose to copy the bell and all conical sections of the horn as faithfully as possible, but to make the instrument in the orchestra horn style, with a small double coil body and terminal crooks and couplers. I felt that this alteration in the configuration of the instrument was justified, because the instrument is unaltered in its bore profile, staying within the acoustical boundaries of the period, and because of the historical precedent of makers doing just this alteration, or variation, with their own models. Johannes and Michael Leichamschneider of Vienna apparently used the same bell and conical tubing design to make large Jagdhorns and smaller crooked horns meant for ensemble playing. In Horace Fitzpatrick’s book, “The Horn and Horn Playing in the Austro-Bohemian Tradition” three Leichamschneider instruments are pictured; a single coil horn in F, a two coil F horn, and a three coil orchestra horn with an inlet for terminal crooks. (the configuration of the last mentioned instrument may not be original) The bells of all three of these instruments appear to be very similar, suggesting that the makers had one horn bell form and possibly one set of tapered mandrels for the other tapered sections, and would make horns in any requested style with these tools. Original crooked orchestra horns from this period are rare, so it seemed the best choice to take this approach, finding an original with the playing characteristics that I liked, and making it in the configuration that I needed, - again not overstepping the design and instrument making practices of the time.

The original of the Haas horn was completely conical throughout, so it was necessary to alter the tapers of the master crooks to accommodate a set of cylindrical couplers used with the orchestra horn pattern. The tapers of the crooks had to be compressed a bit to do this, but this is an alteration that the original maker would necessarily have done if asked to make this horn in the orchestra horn design with crooks and couplers. This has resulted in a crooked orchestra horn that is usable musically, and plays well in a number of keys.

With the exception of the venthole option, the Haas horn is a baroque orchestra horn that is within the believable boundaries of the time, based directly on the dimensions of the original, and makes a sound that is appropriate to the ensembles in which it is used.

Antoine Halari French Classical Horn

To illustrate the process that I go through in measuring an original horn and using the information to have tooling made to produce that model, I will use the example of the French classical orchestra horn after Antoine Halari, from Paris, early in the 19th century, which is reproduced as faithfully as possible from an original in a private collection in the US. It was clear upon playing the original instrument that this horn would meet my musical needs without any alterations whatsoever. This is the most exactly copied instrument that I make, and I hope that if Monsieur Halari were to see one, he would have to study it carefully be able to tell that he didn’t make it. At this point I’ve made over 200 of these and it is being used in just about every period instrument orchestra in the US. But as we will see in the following description of the process of measuring the horn, getting the measurements is only the first step. Making good sense of the information and ultimately making a fine instrument based on someone else’s design involves many elements of actual instrument design and careful working methods.

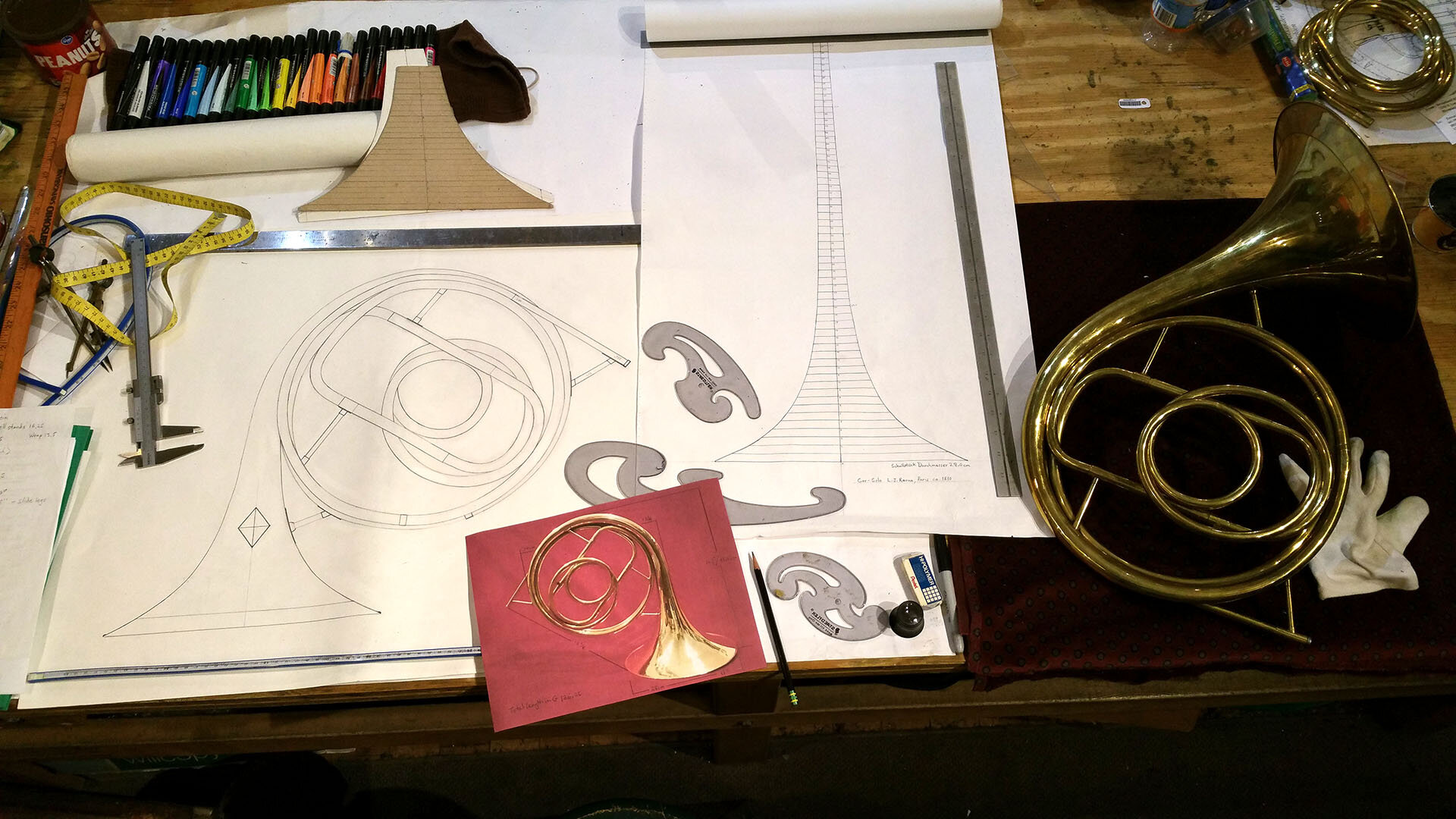

The first task is the gathering of data from the original, which will then be put into a form that can be given to the toolmaker who will make the bell mandrel and other tooling necessary to make the horn. In this case the owner was kind enough to let me take the instrument to my shop for about a month and I had plenty of time to measure it very carefully and take detailed photos.

The bell flare of the horn represents the greatest challenge, and I use several methods to obtain measurements from it. From about 6 inch from the bell flare the diameter is small enough that measuring with calipers is relatively easy and accurate, but the bell flare itself must be measured by some other means to get accurate information. The method with which I have had the best success is to carefully cut a piece of stiff cardboard to fit inside the bell flare, fitting fairly snugly past the 6 inch point up into the bell throat. When this has been cut and adjusted so that it fits reasonably well, I pack modeling clay around the edges of the cardboard so that all gaps are filled and the clay conforms perfectly to the contour of the inner surface of the bell. When this fits perfectly I remove it and trace carefully around it to get a drawing of the profile of the bell. Since the bell flare can deform to a certain degree when the bell is bent, and even more through subsequent use, damage, and repairs, this measurement must be done from more than one orientation. I can then make transparencies that can be laid on top of one another to determine an average contour, - the original uniformly round shape of the bell mandrel on which the instrument was made. This all sounds very primitive, but in 1991 when I did this work it was the only method available. I’m sure there are more high-tech ways to get bell flare measurements today. Whatever method one uses to document the internal shape of the bell, out-of-roundness requires some working with the figures to design a bell mandrel.

The tail section of the bell, the point 6 inches from the bell rim to the end of the bell, roughly 36 inches in this case, can be measured from the outside with a good deal of accuracy with calipers. But the tubing is almost never totally round, due to the fact that when tubing is bent by hand, most often using lead or pitch as a filling material, it becomes oval by a small percentage. Therefore, whenever possible, I try to get measurements in two or more directions that can be averaged together to determine the actual diameter. Caliper measurements are taken all the way along the bell tail every quarter inch, and put onto a chart.

My chart for the dimensions of the bell tail is organized as follows:

The distance from the bell rim is listed first, starting at the 6 inch point. Then in the next two columns the caliper measurements of the outside diameter of the tubing in two directions. The next column gives the discrepancy from roundness and the true theoretical diameter when the two are averaged together. The next column is the rate of growth between points, followed by a revised diameter and rate of growth which makes the taper of the instrument more sensible and smooth. The next column shows how far away these revised dimensions are from the actual measurements taken from the instrument. Since the difference between the actual measurements and revised dimensions averages around .004 in, or about .1 mm, I feel as though I’m not deviating from the original maker’s intentions. Certainly the mandrel on which the bell was made was perfectly round, and the maker intended it to have a smooth, even rate of growth. Variations in the measurements of a bell made from a particular mandrel can result from many things; including the loss of roundness during the bending process as already described, the removal of wrinkles and folds resulting from bending by tapping the surface with a polished hammer or “Auspocheisen”, and the fact that when a straight bell, newly made, is bent, it stretches, and can be as much as ½ inch longer after it is bent. Repairs over the life of the instrument can also obscure the original smooth rate of growth. We can assume that virtually everything that happens to the instrument while it was being made and during its working life alters the dimensions that the mandrel originally gave to the bell of a horn. Therefore I must make some assumptions based on what I know about the working methods of a maker, and how an instrument changes with age.

The numbers in the last row of the chart are those that, after long deliberation, I give to the machinist who will make the steel bell mandrel. These are the revised diameters minus the tubing wall thickness. The final drawing of the bell flare, which is the internal shape, is then matched up to the measurements of the tail section to make a full sized drawing from which the machinist will work.

The other cylindrical and conical sections of the horn are much easier to measure, since their rates of taper are substantially slower in their growth rates, but the basic process is much the same as for the bell. For these sections the measurements can be charted on a graph and refined into a smooth rate of growth. These charts are the final dimensions that will be used to make mandrels for the second branch, mouthpipe, and any other tapered sections of the horn.

The configuration of the instrument and details of construction such as placement of braces, ferrules, and width of the garland are documented through photographs and full-sized drawings of the body of the horn and individual crooks and slides. Then wooden bending jigs can be made. Measurements of the material thickness of braces, sockets and tenons and other fittings are recorded, and patterns made.

In the case of the Halari Orchestra Horn, a model that I make more than any other, - over 200 of them at present, I have drawn full sized patterns of the body of the horn and its crooks on the surface of my workbench and varnished over them for protection. These are used as working patterns in the assembly of the instrument to check alignment and angles. When the mandrels for the bell and conical sections of the body and crooks are finished and wooden bending forms and patterns have been made, I am ready to start making a horn. With all of these items, I can be fairly certain of being able to make the same instrument each time.

A full description of the working methods used in my workshop would be another full length paper in itself, or an entire book that I really should write someday.

The last point I would like to make about the design and construction process is that of the fine-tuning of the design of each instrument. This can only be done by experimenting with the details of each instrument that is made until the design is well worked out and I feel as though the horn is playing as well as it can. Again, this is not a factor of copying precisely what was done on the original, but experimenting with the cut-off points of tapers, where one meets another, placement of braces, angles, heat treating, material thickness, etc. During this stage I am fine-tuning the original maker’s design. As a player I can test instruments in real musical settings and have other natural horn players do the same and give comments, which will help me to improve the next instrument. Being a horn player myself, and working with many fine players has been invaluable in this process.

Working with original instruments in museum and private collections

Another important aspect of examining instruments in collections is the information that a maker can get from them about the working methods of the original maker. A very good example of this is the invaluable information that my colleague Michael Münkwitz from Rostock Germany and I were able to learn from an instrument that Michael discovered hanging on the wall of a country church in the vicinity of Rostock.

The entire story of this important discovery can be found at: www.birckholtz.com

We were able to determine how Birckholtz made his bell and tubing seams, how far up into the bell flare he hammered on the anvil in the construction of the bell, and even some insight into the shape of the pattern that he cut out for the bell. (If, for example, the instrument is made of brass sheet 0.4mm thick and the bell flare thins gradually toward its rim to a final thickness of 0.2mm, one can assume that the pattern at the bell rim was roughly half of the finished circumference when first seamed up. We were also able to determine that this instrument was probably never altered, or had any substantial repairs done to it.

Scraper marks gave hints as to the original surface finishing of the brass, and careful examinations of the decorations helped us to make the steel stamps and engraving tools to reproduce the instrument. This trumpet in its unrestored condition yielded much more information than if it had been restored to playablity.

What information and documentation can a museum collection do that is of use to instrument makers?

Drawings and measurements carefully and completely done by instrument collections are rare, and the only instrument that I’ve wanted to copy for which this has been done was the Hofmaster horn in Edinburgh. Sets of full scale drawings, photos, and tables of dimensions that are available to the public are extremely helpful.

Recordings to document the sound of instruments along with evaluations of playing qualities by players are also helpful. My wife and I were recently involved in recording short examples on the horn family instruments from the Joe Utly collection in South Carolina, which will be a permanent documentation of the sound of these instruments.

Most collections have specific policies on playing originals and measuring. I am probably a bit biased on this point, but I think that for the purpose of gathering information for copying an instrument, or for a recording, a minimal amount of playing on an historic brass instrument is worth the minimal amount of wear that the instrument will suffer on that one occasion.

Even though I like to be able to play an instrument to decide if it is worth copying, I feel as though I can often get more information from an instrument in its unrestored condition. When an instrument is not playable it is often best, for the maker’s purposes to simply leave it as is.

And lastly, from the maker’s side of the relationship, I think it is important for many reasons to acknowledgment of sources of information and the collections where the originals are located in advertising material and websites.